accesses since July 22, 1996

accesses since July 22, 1996 copyright notice

copyright notice

link to published version: Communications of the ACM, October, 1996

link to published version: Communications of the ACM, October, 1996

accesses since July 22, 1996

accesses since July 22, 1996

With the U.S. Presidential election upon us, it may be useful to reflect on the political future of cyberspace. An exciting new technology like the World Wide Web is simply too much for a politician to overlook. Attracted to the hype like moths to flame, politicians throughout the computerized world seek to establish a presence on the Web - in many cases before they connect their offices to the Internet.

There is nothing inherently wrong with politics on the Web. The Web, and other Internet resources, are tools which may be used to better connect the voter, the politician and the issues. Nothing wrong there.

In fact, digital networks could actually help enlarge the informed electorate. While most of the requisite technologies have been around for some time, they have been largely ignored by politicians. E-mail - a technological staple of the federal (and most progressive state's) Governments for several years - has heretofore been used primarily as an internal communication medium by politicians and their staffs. Now that the citizenry is going digital, the constituent e-mail will begin to flow - which will quickly produce an unexpected new source of information overload for the unwary politicians.

In any event, the Internet revolution has the ability to change the nature of the political communication from internal, organizational, and private - as it is now - to external, constituent-based and public. One-way political pronouncements might evolve into two-way political dialogs. Democracy may never be the same again. Perhaps.

As happens with any emerging technology, the technological imperative is rearing its ugly head. This imperative compels us to use technologies for their own sake - for no other reason than we know how. The lure of the exciting and new seems somehow more gratifying than the time-honored, enduring rewards of old.

So it is with politics on the Web. After visiting a few hundred political Web sites, the adjective "uninspired" comes to mind. Political Web sites at this writing seem to fall in the middle of the Web content/quality continuum; securely nested in what Howard Rheingold calls the "document phase" of the Web experience, where the focus is primarily on multimedia display to the exclusion of interactivity. And even at that, current political multimedia leaves something to be desired.

But the growth of generic multimedia is really not the problem with the political part of cyberspace. There is a real possibility that that ever-pragmatic politicians will follow the lead of the direct marketers to use the digital networks primarily for electronic junk mail and digital billboards. Political staffers may soon narrowcast and broadcast their political messages to the farthest reaches of cyberspace. Of course, the use of the networks as a mass-marketing tool is not only an under-utilization of the technology, but also a tremendous abuse of the electorate.

I see at least three potential problems with the use of the Web as a propaganda vehicle, all of which could have potentially serious social consequences.

The least harmful of these is the additional proliferation, far beyond the mandate of need and good taste, of cyber junkmail. Were future political junkmail to further de-sensitize us to the enormous collective time hit that such media take on us, society will be worse for the experience.

A far more onerous problem is that over time politicking on the nets may actually further rectify the information flow between politician and the body politic. That is, future cybernation could easily evolve to the point where canned, tailored responses can be crafted for individuals and groups of all stripes and sizes - with less human intervention than common sense and good government dictates. Such automation could ultimately elevate spin-doctoring to an art form as each ethnic and socio-economic group hears their customized, spun-doctored version of the party line.

Third, there is the "noise factor." Unlike Gallo wine, political discourse, especially in the form of speech and press release, tends to get released before its time. Try to recall memorable political speeches. Stripped of the audible and visual components, the actual content of political speeches tend not to, and for good reason, reside long in the public mind. I suspect that, for most of us, the more memorable speeches were committed to memory in grammar school - except, perhaps, for a few which might have been especially humorous or embarrassing to the speaker. Any technology which encourages more political rhetoric for its own sake is likely to work against the common good. The health and well-being of our political future lies with dialog and not declamation.

Political rhetoric also doesn't seem to scale well. Unlike the finely crafted poem or novel which withstands analysis, and indeed reveals insights and understandings, at a number of different levels, political discourse tends to degrade as it grows. The clever, cogent sound bite more commonly begets confusion than argumentative depth as it expands. That may account for much of the negativity in political campaigns - it's easier to produce in quantity than compelling argumentation. In any case, when it comes to political talk, the incontrovertible sentence tends to grow into the dubious and inconclusive paragraph.

In addition to propagandizing on the Web, a second potential abuse is the invasion of privacy. As anyone familiar with Web technology may attest, the use of CGI and SSI environment variables to determine and catalog the user's name, IP address, e-mail address, operating system type, name and version of browser, local time, and the URL of the previously visited Web site that links to the present site, is easily accomplished. This information may be effortlessly collected in, and shared between, a multitude of databases and electronic mailing lists. While it certainly seems within the sphere of the Web's de facto standards of fair use to keep track of this information to help improve Web services, I'm not sure that many Web users would agree that fair use entails using this information for political purposes. But it can be done easily, and probably will be.

So it is far from obvious that this increased political connectivity will necessarily be in the public interest. The price which society will have to exert to avoid intrusive abuses such as those mentioned above will be perpetual vigilance.

At this writing, politicians and political organizations have yet to take advantage of the interactive and participatory capabilities of the Web. Most political sites are passive repositories of staid media with an occasional interactive form. The Clinton/Gore White House and Dole for President Web pages are illustrative of the more polished political cyberspheres.

Befitting a sitting President, the White House cybersphere is fairly rich in content. In addition to the traditional political fare of white papers, speeches, policy statements, lists of accomplishments categorized by affected state, and so forth, there are useful public-domain resources: portrait galleries of former presidents with attached biographies, guides to Federal services and resources, an annotated Declaration of Independence, and a collection of White House documents, to name but a few. Sitting Presidents can console the nation in times of grief, open olympic games, keynote meetings, and fill cyberspheres with government resources. The advantages of incumbancy will apply to cyberspace as they do in other aspects of political life.

From a technical point of view, the White House homepage appears respectable, though generic. The splash page has the pro forma gratuitous Java applet - to which so many of us succumb nowadays. In this case the applet presents dual, unfurled American flags undulating in the virtual digital breeze alongside a tasteful color photo of the White House, set in relief (see Figure 1). In addition, CGI scripting changes the welcome from "good morning" to "good afternoon" to "good evening" (unfortunately, only at the correct time of day for those in EST) and updates the White House photo with one with appropriate shadowing and light. Like the Dole cybersphere, however, there is no advantage taken of the later Netscape extensions, frames and plug-ins.

To illustrate that there are still many slips twixt cup and lip in the Web development game, until very recently the White Hose homepage restricted audio offerings to Sun AU files used primarily on Unix workstations. According to the Fourth Web Survey, this amounted to only 6.8% of Web audience. WAV would seem to be the more reasonable format given that 61.5% of the Web clients seem to be running Windows. A recent expansion of offerings includes Real Audio, but still no WAV. The Administration doesn't seem to understand that most of the hoi polloi won't go to the trouble to install a new audio player in their Web browser's launchpad just to hear the Prez reflect on Bosnia.

The Dole for President cybersphere attempts to achieve much the same effect as the White House, but through a linear interface (see Figure 2). Sensitized icons along the left side of the homepage offer the same range of information as the White House. However, where the White House can offer indexes to White House and Federal documents, candidate Dole is limited to offering Dole trivia quizzes and a potpourri of Dole for '96 screen savers. The campaign advantages which accrue to sitting Presidents with easy access to Government resources are made especially obvious in cyberspace.

Technically, the Dole homepage is about as mainstream as that of the White House. The differences are that Java script (Dole) substitutes for Java applets (WH) and lip service is paid to HTML 2.0 compliance as different cyberspheres are offered according to whether the user hosts a Netscape 2.x-compatible Web browser (not in WH). Our inspection didn't reveal any support of frames, applets, plug-ins or any of the recent technological extensions supported by Netscape.

We note that as of this writing (early July) Perot's Reform Party Website (http://www.reformparty.org/) remained impoverished for want of candidate.

The central concern that I have for future use of the digital networks for political end is that it will become but a cheaper and more efficient means of propagandizing via direct e-mail supplemented with occasional dynamic Web documents and interactive forms.

However, there is the possibility that politicians will eventually come to understand that the potential of the Web resides in interactivity and in the possibility of greater individual participation in the political process. There are several opportunities in this regard which shouldn't be overlooked.

Digital connectivity, through Web-like protocols, may provide the electorate with unparalleled political accountability. Modern network databases, indexing tools and search engines could penetrate politics and government to the point where every congressional vote can be cross-indexed by topic, theme, political party, outcome and elected official. Just imagine - voting records on demand, in real time and cross-indexed. Patterns of poor or self-serving judgment might actually be discernible before crises develop. The public might have the opportunity to react to the pork barrel, the log roll, paired voting and patronage appointments before they became fait accompli. Political malingering and double speak could be identified as such. It would become almost impossible for politicians to enjoy the anonymity which a forgetful electorate permits.

Over time, there would emerge a political memory which will be unfailing over time, unforgiving of concealment, and intolerant of deception. Politicians might become more circumspect when they realize that each one of their constituents could have perfect digital recall through the Web.

While it would be naive to assume that many citizens would actively use the digital network resources to monitor political performance, that wouldn't be necessary. The accountability would be achieved through the increased scope and depth of reporting by the fourth estate. As the Watergate experience revealed, the difficulty in exposing abuses of government are not due so much to the absence of information, but rather to the difficulty journalists have in collecting, integrating and assessing diffuse information from variegated sources in a timely fashion. It has taken twenty years for journalists to assemble a relatively complete story of Watergate on which the surviving principals seem in agreement. Political accountability and journalistic efficiency are wed in this regard.

Modern network technology allows us to have group conversations where political ideas and notions can be exposed, rebutted, revised, refuted and rejoined to any desired degree. An enormous opportunity for high-fidelity decision making awaits the politicians and political organizations who can figure out how to harness this interactivity without drowning in it. However, this won't just happen automatically because there is precious little wheat amidst the group-speak chaff. Success in this area will require both considerable technical skill and a significant investment of time and money, but the rewards could be revolutionizing.

Lacking the technical sophistication to take advantage of the technology, we predict most politicians will only pay lip service to this level of interactivity.

The weakness of modern participatory democracy is that it isn't all that participatory. Active participation requires time, energy, commitment and, most of all, the belief that the participation is likely to have some beneficial outcome. This last point must not be overlooked as now nearly half of U.S. citizens fail to vote in national elections for they feel they have little to gain or lose in the outcome. Over time participatory democracy has degenerated into rule-by-influential-minority. But it doesn't have to be that way, and the Web can help reverse the trend because it can eliminate many of the obstacles between the citizen and participation in the political process. The social costs of participating in digital democracy are low.

Not to be overlooked is the extreme ease with which digital balloting may be implemented on the Web. Santayana's dictum about learning from past mistakes is relevant here, lest the phrase "digital election fraud" enter our vocabulary. Western democracies have begun, just in the latter part of this century, to achieve a high degree of integrity in the voting process. Our challenge will be to see if we can port this over to the networks without problem through programs and procedures which will ensure that voting remains untraceable under authentication.

Accomplished from home or office, such "no pain" voting is certain to have a major impact on both the political and electoral processes.

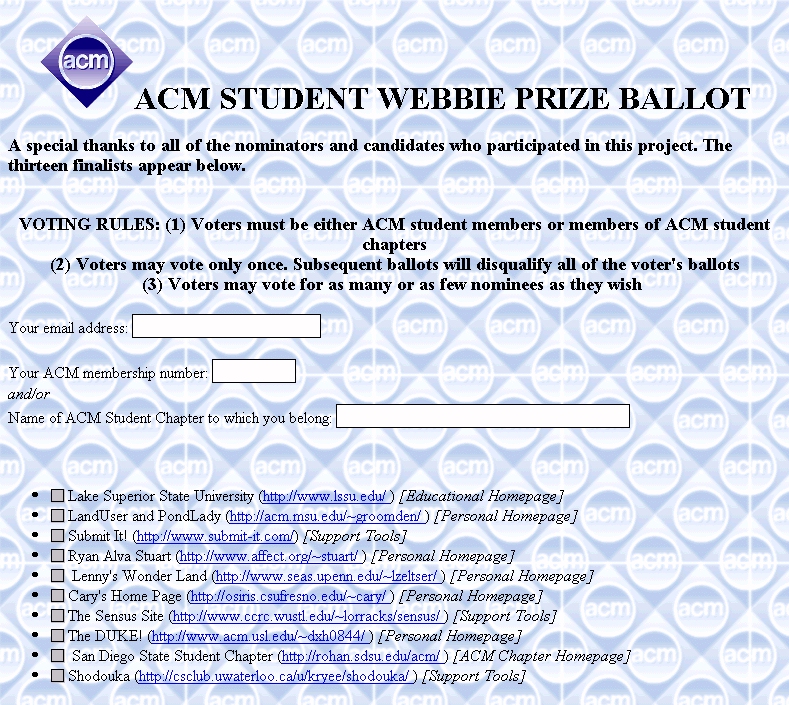

Incidentally, the ACM actually uses a primitive form of a digital ballot box in conducting the nomination and voting for the annual Student Webbie Prize for student achievement in cyberspace (http://www.acm.org/webbie/).

Of course the digitization of politics will not be a panacea. It will not just reduce or eliminate current political problems, it will also spawn new ones. This is the inevitable price we pay for technological advance. As the automobile contributed to the homogeneity of nations, it also facilitated the growth of the suburbs and the eventual decay of the inner cities. The great challenge before society is to ensure that the new problems are easier to deal with than the old.

Digital politics may also contribute to the balkanization of the electorate. The ease by means of which electronic communities may form would actually tend to encourage this since geographical constraints are absent in cyberspace. As these "digital enclaves" spawn, new strategies will have to be developed to nurture consensus.

It also remains to be seen whether, or to what extent, virtual communities will figure into digital politics. Our observations are neutral in this regard. We are looking at the digital politics through the lens of technological capability as it augments a traditional political process. There is another perspective which derives from the study of society and on-line social movements. Studies into the nature of on-line inter-personal and group relationships, and the degree to which these relationships are sustainable in cyberspace, are also relevant but beyond our ability to assess. For answers to these and other pressing problems we must ultimately turn to sociology and psychology.